In an interactive livestream conversation hosted by Native American Yale Alumni (NAYA), Annette Saunooke Clapsaddle ’03, the first enrolled member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI, one of three federally recognized Cherokee tribes) to publish a novel, discussed her experiences and evolution as a writer, Native Americans in publishing, and the importance of storytelling in Native American culture.

Moderating the conversation was Ashley Hemmers ’07, the chair of NAYA and chief administrative officer of the Fort Mojave Indian Tribe, a sovereign nation based in a tristate reservation in California, Arizona, and Nevada.

NAYA is the shared identity group dedicated to connecting and strengthening the Yale Native community.

The former executive director of the Cherokee Preservation Foundation, Clapsaddle has been an educator for a decade and currently teaches English and Cherokee Studies at a high school near where she was born and raised in western North Carolina. She said that while teaching is her foremost passion and calling, she has been an inveterate writer since elementary school and, on a professional level, has authored everything from poetry to children’s books to nonfiction. And, now, fiction.

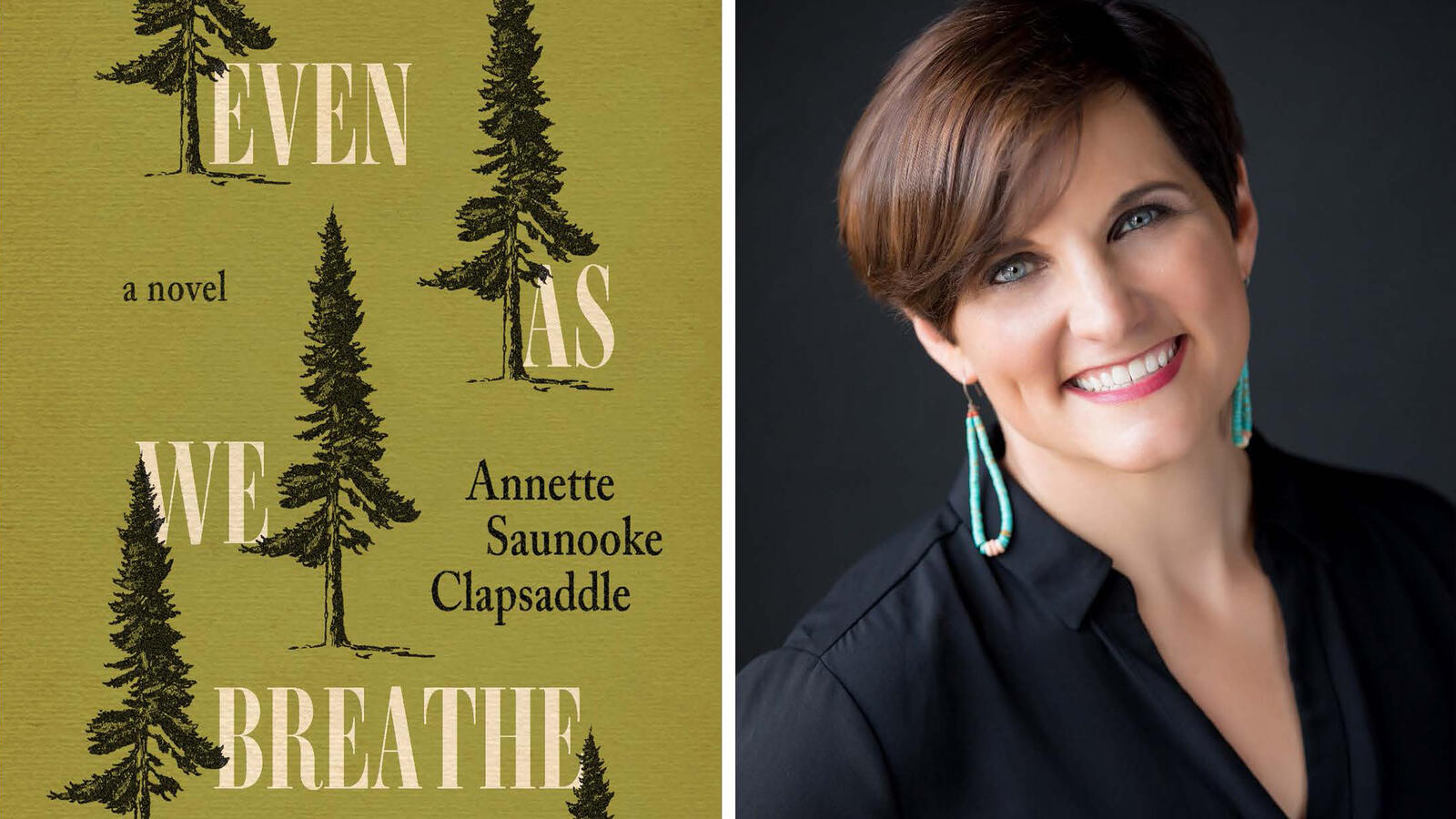

“Even as We Breathe,” her debut novel, published in September, is about a young Cherokee man who, eager to escape his hometown in North Carolina, takes a summer job at a resort where Axis diplomats and families are being held as prisoners of war during World War II.

Clapsaddle said a major motivation for her as a writer is to create works that resonate strongly with her students and characters with whom they can identify.

“I always have my students in my head in terms of audience,” she said. “I want them to see themselves in the narratives.”

Identity, family, place, sovereignty, racial dynamics, and belonging were among the themes she explores in her writing – themes that evoke important questions and discussions in Native American communities, like, “What does it mean to be a citizen of the United States when often times your citizenship is questioned?” she posed as an example.

Clapsaddle said she feels a special obligation to write about her community, whose members rarely, if ever, see, hear, or read about themselves, their lives, or their culture in mainstream media or popular culture. Highlighting this point, she quoted an EBCI student who lamented, “People just don’t write about folks like us.”

Not if she has anything to do with it, declared Clapsaddle, who added that there is no shortage of experiences and stories she can share as a writer.

“There are plenty of stories I feel led to tell about where I’m from,” she said.

On Storytelling

In discussing the prominence of storytelling in Native culture, and its significance as a cultural heritage and tradition, Clapsaddle recounted that it was a constant in her life growing up – and continues to be a regular feature at family events and gatherings.

“It’s very common to go to a family gathering and people will be sitting around and launch midstream into a story you didn’t realize was gonna be a whole thing,” she said, joking that this is one of the reasons why family gatherings, and conversations with family members, can become long, drawn-out affairs.

Humor aside, she extolled that storytelling goes beyond mere entertainment and rote tradition. It continues to play a crucial role in imparting knowledge, history, values, wisdom, and life lessons – something she believes is not exclusive to Native communities.

“There has always been a sense of storytelling in my community to teach value systems and life lessons,” she said. “And that’s not unique to Native communities; all communities have that type of storytelling.”

She was mindful, however, that storytelling in Native culture tends to get romanticized and stereotyped in pop culture – she mentioned the common scene portrayed in the media of elders sitting by the campfire telling old stories about how the world began – and cited this as both a challenge and an imperative for Native American writers.

“It’s one thing to tell, ‘Oh, this is what happened,’ and to tell it in a structure that’s typical for mass media,” she said. “But it’s another to embed our value system in the voice that is telling the story.”

On Writing and Native Writers

In responding to questions about her writing process and tips and advice for other writers, Clapsaddle emphasized the importance of writing with an authentic voice that is distinctively and uniquely one’s own, and to avoid mimicking or copying other writers.

“Don’t try to write like anybody else,” she said. “As a teacher, I don’t try to teach like anybody else, and I can’t, and nobody can teach like I teach, and I think the same is true for writers.”

She added that getting the voice right – one that connects strongly with readers – is particularly important in novels and advised writers to think carefully about the development of their characters.

“Make sure you know the motivation of your characters,” she said. “Every character will have a motivation and it will drive the action.”

She added that writing, as a craft, is an iterative and sometimes painstaking process that requires discipline, perseverance, and the ability to humbly receive creative input from others.

“You can’t get confidence if everybody is telling you that ‘it’s great, it’s great,’” she said. “Confidence really comes in the critique and working through that critique.”

While concerned that Native American writers continue to constitute a very small cohort within the literary world, she was encouraged that more of them are getting published and, increasingly, their voices, experiences, and stories are getting heard.

“Every Native community is different,” she said. “There is enough room in the publishing industry for all those different stories.”