I attended Yale undergraduate classes from 1963 to 1965, the only woman in my classes.

This was before Yale officially admitted women, and as such, I was not an official student, though I felt like one. I was the wife of a graduate student, Thomas Curtis ’68 PhD, and a mother. I really wanted a college education, and with the help of my husband's all-male undergraduate college, Kenyon, and of the graduate school of physics at Yale, I was able to do so as an auditor.

I took the best lectures on campus (as advised by a Skull and Bones man then at the law school). I learned more of what was best about Western civilization and also assimilated the implicit societal lessons addressed to male Yalies, of responsibility and leadership in America. As I drank in the Gothic atmosphere and enjoyed Sterling Memorial Library, homage in itself to knowledge, I felt akin to males my age. I paid attention to our culture, our government, and our country's place in the world, as well as our own responsibility to contribute, support, and lead.

These courses help explain that Yale message of the appropriate role for the generation of students:

- Tragedy: Who was heroic, what were the stakes, what were the dilemmas, and how far did the hero fall? Professor Richard Sewell set forth the standards for us – not only an examination of the tragic, but a setting forth of admirable or problematic behavior and responses.

- Art and Architecture of the Western World: Spanning from Greek and Roman antiquity through the centuries to modern architecture and urban renewal in America, the question was: What was beauty and man's appreciation of it? This was brought to the streets of New Haven as we, under the tutelage of Professor Vincent Scully, analyzed the physical experience of a city block.

- 19th Century British Novel: The English novel focused on the individual caught in social dictates of England. Our professor, probably to entertain the male class, told ribald tales; I responded by sitting in front of him the entire class. The point was human comments on life through novels and the power of an individual's voice to state truth in writing.

- Existentialism: It was like taking a class at the Sorbonne to have Professor Henri Peyre review works of authors such as Sartre, Gide, Camus, Ionesco, and Genet. Peyre may, or may not, have discussed Simone de Beauvoir's "Second Sex," but he did take me to President Kingman Brewster and suggest that I become the first female graduate of Yale. The book, "L'Etranger," was how I felt at Yale: apart.

- Modern American History: This course filled the young men in on what had transpired and what they were expected to do. I looked over that huge crowd of young men in their tweed coats and ties, sitting alert to hear Professor John Blum's words, and wondered how many would in fact be leaders. (George W. Bush ’68 may have been in that class.)

While I did not know many students or engage in Yale's activities, I did enjoy the Long Wharf Theater, Ingmar Bergman at the local art film house, polo on Sundays in Purchase, N.Y., sailing at the boathouse and avoiding rocks in the Sound, attending concerts (Peter, Paul, and Mary) and Yale football games, and making furtive trips to a night spot playing blues on Dixwell Avenue.

In the spring of 1964, we in the Paul Rudolph Married Student Housing danced weekend nights to the Beatles (and saw them at their first concert in Queens). For a while, we were official chaperones for Yale fraternity dances and the prom, probably as we were young and would not dampen the fun (yet I was concerned about a Jerry Lee Lewis performance at a fraternity).

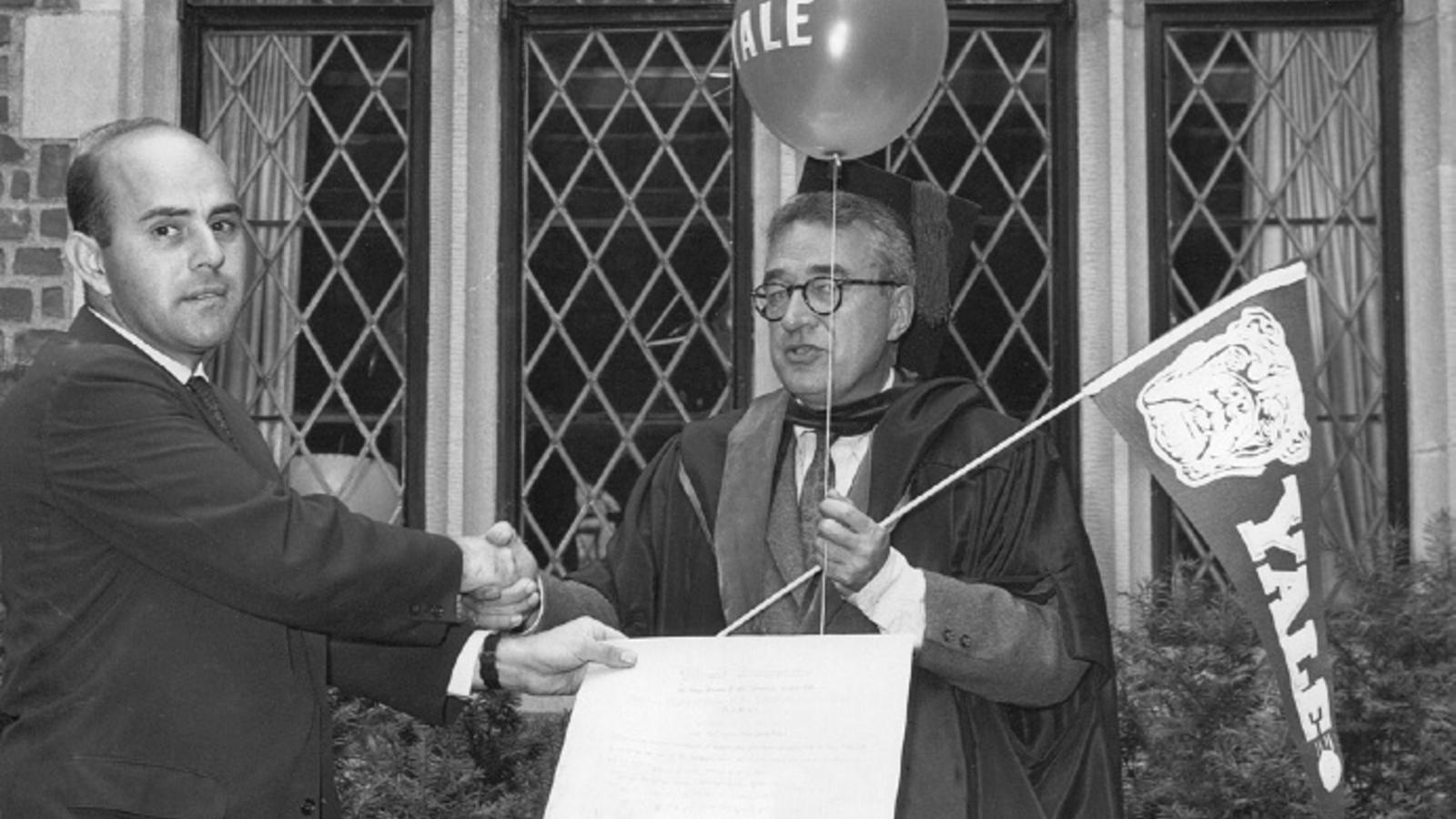

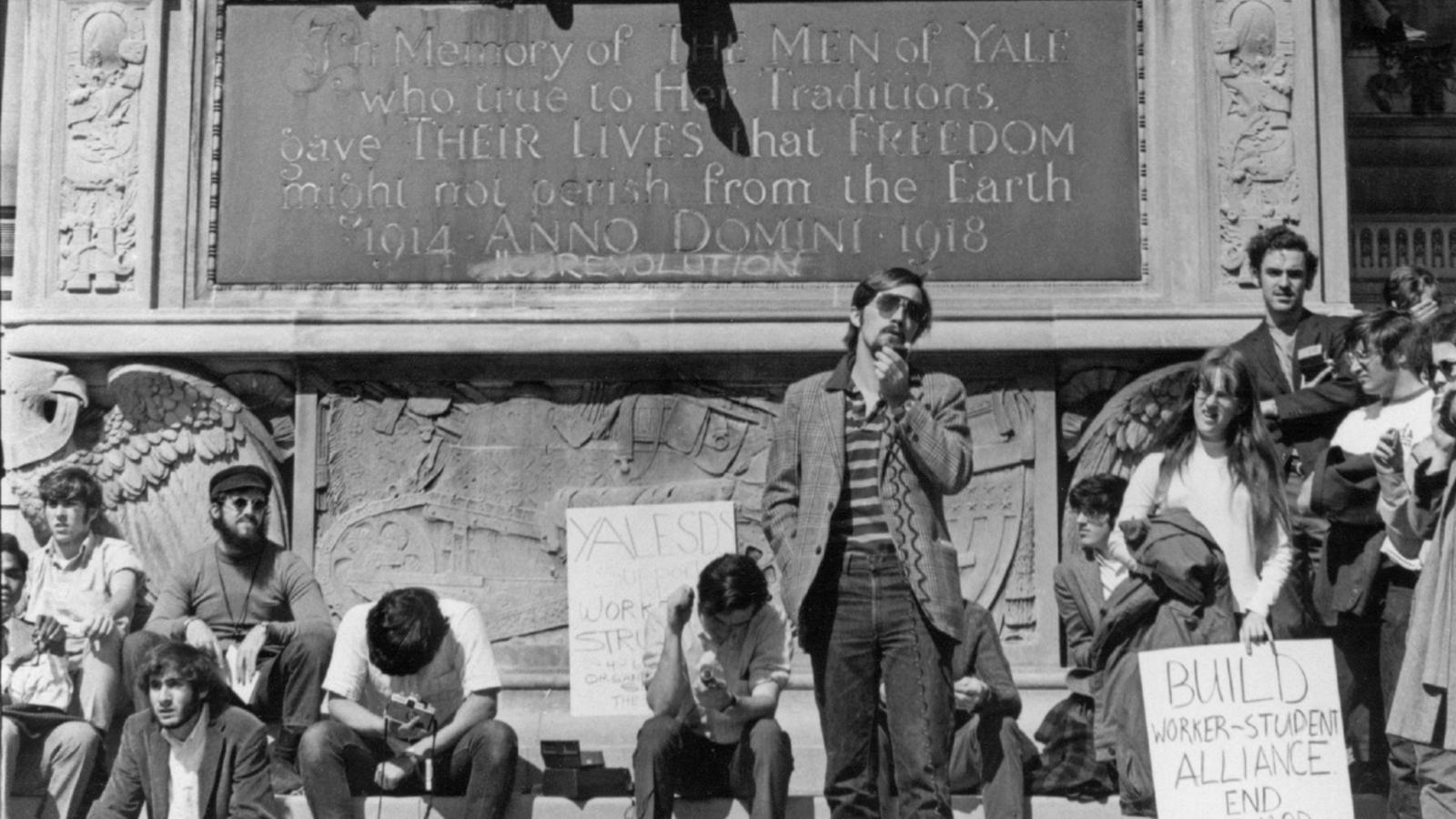

So far, this was all 1960s normal. But change was in the air. The Vietnam War was ongoing, and the Reverend William Sloane Coffin was a vocal participant in expressed opposition. There were demonstrations, many on the New Haven Green. The separation of the sexes was being rethought by academic institutions, and there were discussions about Yale merging with Vassar, a female college at the time.

I was told I could not get a Yale undergraduate degree because I was female, even though I had written papers and taken exams for the Yale courses. I could continue on to get a Yale master's degree, but I would have to go through life explaining why I had no undergraduate degree. This was deemed an insurmountable hurdle in the mid-60s, so I approached Vassar, which let me commute, take a reduced course load, do independent study in the summer, and gave credit for my prior college work at yet another institution and credit for my Yale work.