According to the United Nations, there are more than one billion people with disabilities, or roughly 15% of the global population. The UN also attests that people with disabilities are disproportionately impacted by climate change and natural disasters.

In a recent livestream forum led by Yale alumni, an international panel of experts, practitioners, and scholars held a dialogue on the intersectionality of disability and climate change, including discussions on current environmental policies, exclusionary planning and infrastructure, and ways to build a more sustainable and accessible world.

The program was hosted by the Yale DiversAbility Alumni Group (YDAG), an emerging shared interest group that connects alumni with disabilities (and allies) and galvanizes support to advance and improve accessibility within the Yale community and beyond, and Yale Blue Green (YBG), Yale’s environmental alumni organization.

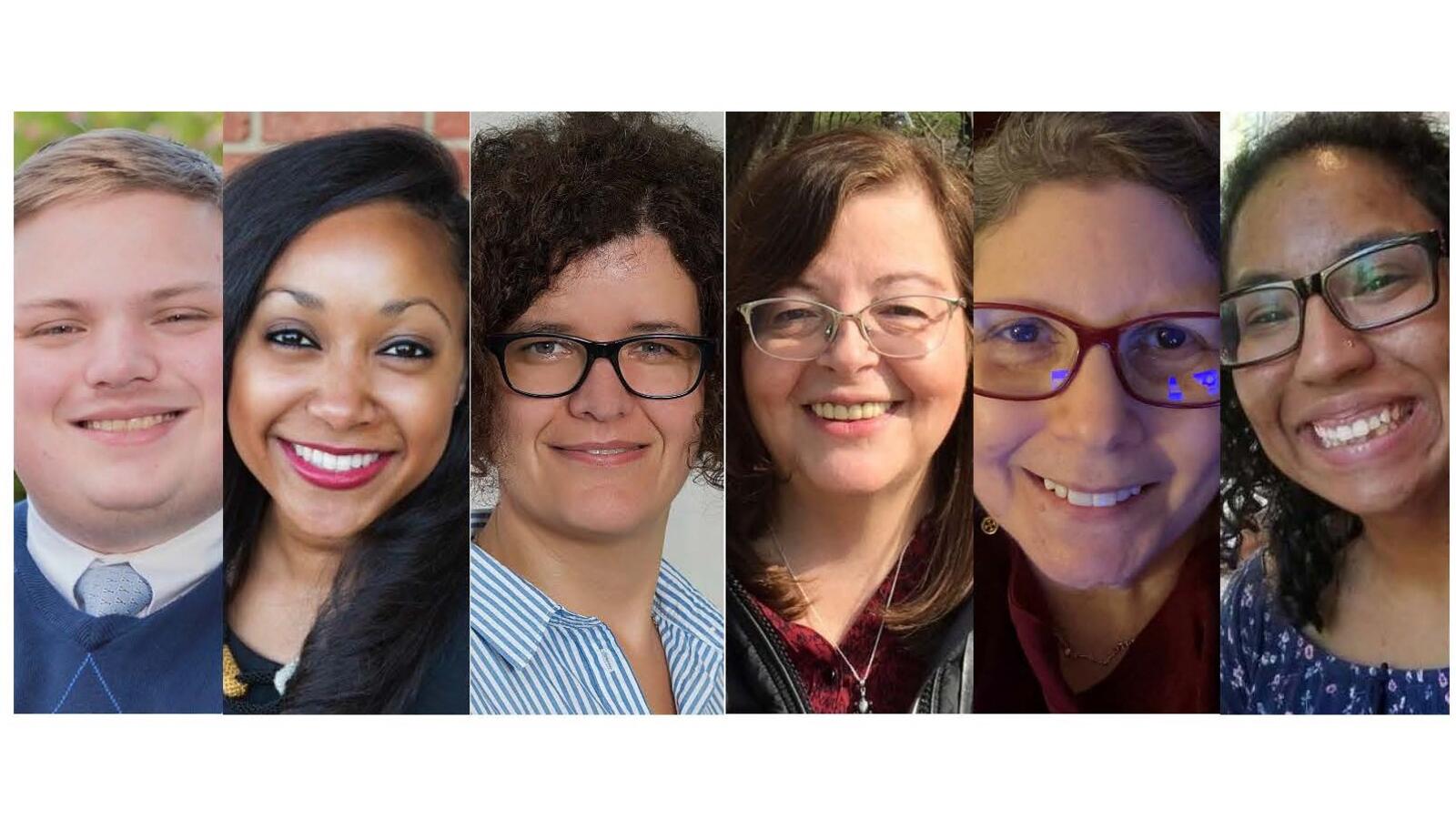

Moderating the forum were Benjamin Nadolsky ’18, co-chair of YDAG, and Lauren Graham ’13 MEM, chair of YBG. The lineup of speakers consisted of:

- Sasha Kosanic – Lecturer/Physical Geographer, Liverpool John Moores University

- Yolanda Muñoz – Project Coordinator (Disability-Inclusive Climate Action Research Programme), McGill University

- Valerie Novack – Disability Policy Researcher; Ph.D. Candidate (Land Use Planning and Management/Development), Utah State University

- Marcie Roth – Executive Director & CEO, World Institute on Disability

Climate Justice for All

There was unanimity among the panelists that besides being disproportionately impacted by hurricanes, floods, droughts, heat waves, and other natural disasters, people with disabilities often fall through the cracks in getting support and assistance during climate crises.

“For people with disabilities, climate justice has almost always failed to be inclusive of accessibility,” said Roth, who previously served as a senior advisor on disability issues to the administrator of the Federal Emergency Management Agency. “They’re denied a kind of equity right.”

According to Kosanic, who has explored gaps in climate change research, it is not surprising that emergency management efforts often fail to address the needs of people with disabilities since their input, advice, and guidance are rarely, if ever, elicited – much less incorporated – in disaster planning and practices.

“We really need to understand what services disabled populations need and how we can deliver these services, but also how we can protect these services,” she said, adding that addressing these needs would improve climate change adaptation and mitigation efforts for society as a whole.

Kosanic pointed out that based on the Sustainable Development Goals adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2015 as a shared blueprint for the international community to achieve a better and more sustainable future, failure to consider and include people with disabilities denies them of human and civil rights intended for everyone.

“If we look at sustainable development goals, they’re for all. We cannot leave anyone behind,” she said. “So if we really want to reach sustainable development goals, we need to include disabled populations in active discourse.”

Bad Policy to Blame?

Novack, whose area of expertise includes environmental planning and building resilient community policy, said that non-inclusive policies significantly exacerbate the impact of climate disasters for the disability community.

“A lot of outcomes that results disproportionately in disabled people dying are not the result of climate change,” she said. “They’re the result of policy and they’re the result of practices that we’ve put in place.”

She added that cultural and societal biases are also important factors.

“When I look at what the risk is to disabled people, I really think our prevailing ableism and lack of value of bodies that do not function in a certain way is the biggest threat of climate change,” she said. “As long as we keep that mindset, whatever progress we make in addressing climate change is still not going to fully protect these vulnerable people because we’re not doing it for them.”

Muñoz, who as a disability rights advocate works with indigenous communities impacted by climate change, said that even in cases where members of the disability community are asked to wade in on climate policies, this inclusion tends to be more superficial than substantive.

“There is this tendency to include a list of marginalized populations in strategy and policy, but it’s merely symbolic, it’s discursive,” she said. “And this is very dangerous because the decision makers and policy makers are assuming that they are being inclusive only because they mention disability, and gender and marginalized populations, but there is nothing that specifically addresses what needs to be done.”

Muñoz warned that as climate disasters proliferate, along with armed conflicts over land, water, and other natural resources, people with disabilities will continue to face enormous challenges. She added that those who become displaced due to climate disasters could easily find themselves discriminated against and denied refuge within the international community.

“We have immigration policies that actually reject applicants with disabilities,” she said. “What will happen when people have to leave their lands and relocate?”

Moving Forward

Mindful of the challenges in building a more sustainable and accessible society, the panelists shared their insights on different options and approaches.

Roth opined that within the U.S. context, rewriting or adding anti-discrimination laws and legislation would not necessarily produce significantly better climate justice outcomes for people with disabilities.

“I would not suggest that we open up the Americans with Disabilities Act or that we try and write a better civil rights law. The Act is an amazing piece of legislation, absolutely amazing,” she said. “But there has been a nonstop failure to implement the law, to monitor its implementation, to enforce what is required.”

Novack pointed out that like COVID-19, natural disasters and climate change are not restricted by geography and do not discriminate on whom they impact. Accordingly, a robust and coordinated response by the international community is required.

“The realities of climate change are going to get to a point where we are no longer going to have these fanciful arguments about whether or not this is something we should be worried about because we’re seeing it in real time,” she said. “We’re learning and having to readjust to the fact that we really are interdependent and interconnected with one another.”

According to Muñoz, the disability community will need to continue to push hard to dismantle ableism and bolster its efforts on disaster risk readiness if it hopes to realize climate justice.

“Our responsibility as persons with disabilities – to be more informed, to be more proactive, to elaborate more solid advocacy strategies, to ensure that there will be actions that will actually take us into consideration,” she said.

She noted, however, that given the ubiquity of disability and the increasing prevalence of natural disasters and climate change, the fight for climate justice is truly a struggle that must be undertaken by everyone.

“Disability has very fluid limits. Disability happens in life,” Muñoz said. “So it is important for everybody to get rid of all the prejudices, the fears, the tragedy, all that stuff, and understand that this is a matter of social justice.”