In a livestream event hosted by Yale Blue Green (YBG), Yale’s environmental alumni interest group, a panel of four Black environmental leaders engaged in a candid dialogue about their personal experiences and professional trajectories in the sustainability space; the deep legacy connections that Black people have with nature, land, and water; and biases and inequities in the environmental sector.

Entitled Black in Nature, the program was organized by Georgia Silvera Seamans ’01 MEM, an urban forester and YBG leader based in New York City, who felt strongly that such a discourse was necessary in light of the coronavirus pandemic and the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests sparked by the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and others.

“Both laser focused my attention not only on Black ecology but [also on] Black people’s diverse and deep relationship with nature,” said Silvera Seamans.

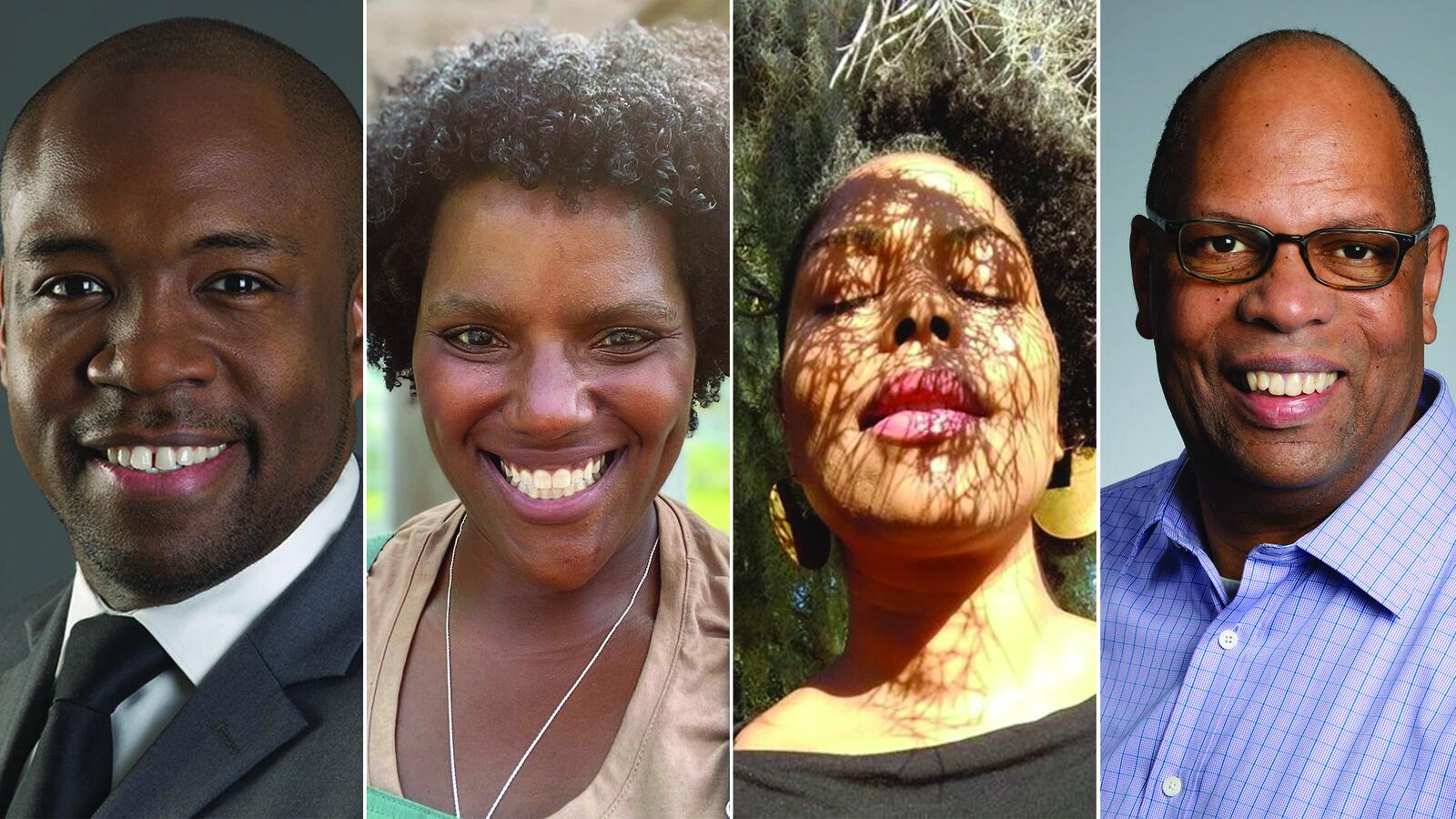

The panel consisted of speakers from academia, the public and non-governmental sectors, and the faith-based community:

- Thomas Easley (moderator) – assistant dean of community and inclusion, Yale School of the Environment (formerly Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies)

- Michelle Lanier – director of North Carolina Historic Sites; adjunct faculty, Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University; executive producer, Mossville: When Great Trees Fall

- Rev. Dr. Michelle Lewis ’13 MESc/M.Div. – public theologian, radio personality, writer, environmentalist; executive director, Peace Garden Project

- Charlie Nilon ’80 MFS – William J. Rucker Professor in Fisheries and Wildlife, School of Natural Resources at University of Missouri

Fully aware that the number of Black professionals in the environmental space is small, the speakers conveyed the importance of their upbringing and childhood experiences in influencing their career paths.

Easley credited his grandparents for fostering in him a love of nature and teaching him how to “plant and eat off the land.” His passion for the environment led him to join the Boy Scouts of America and propelled him to achieve the highest rank attainable, Eagle Scout, an accomplishment for which he remains proud of today.

Nilon learned to appreciate nature as a youth through walks with his father and dog, and hearing about his father’s childhood experiences in rural Alabama. Growing up in Colorado, he fondly recalled how “all kinds of people” were able to enjoy nature and had access to outdoor activities like fishing, hiking, backpacking, and swimming.

Lewis attributed her early shaping as an environmentalist to an Earth Day program at an aquarium, but it was a seasonal job with the U.S. Youth Conservation Corps at the age of 14 that had a more significant impact — this experience led to other related employment opportunities that eventually launched her into a permanent position and a career with the U.S. National Park Service.

Being Black in Green Spaces

Each of the speakers shared their experiences of being either the only Black person or one of a handful in their workplaces, and the general lack of diversity in the environmental sector.

Lanier, who is the first African American to oversee all museum spaces, battlefield sites, and historic landscapes in North Carolina, works with a predominantly white staff. In her position, she also exercises a leadership role over the state’s capital, Raleigh, which has a direct connection to the commemoration of the Confederacy.

For her, the intersections between the Confederacy, slavery, BLM, and growing calls to take down Confederate monuments go beyond her professional responsibilities. Lanier revealed that prior to the BLM protests, she discovered a surprising genealogical connection through a DNA test.

“I am the descendant of a Confederate officer who did not claim his Black family,” she said.

Nilon, who has spent most of his academic career at the University of Missouri, lamented that the university has essentially the same number of Black faculty that it had more than 30 years ago when he arrived, and the same number of Black students.

During her career with the Park Service as a law enforcement officer, Lewis said she didn’t see many people of color. She described how she became a curiosity not only among her colleagues but also to visitors at national parks where she was assigned — people would often ask to have a photo taken with her because of the novelty of meeting a Black park ranger.

According to Lewis, when she left the Park Service, there were about 3,500 law enforcement officers and only 10 were Black — two of whom were women, including her.

Effecting Change and Inclusion

Recognizing that the environmental sector had a long way to go before it fully reflects the richness, diversity, and talent of the nation, the speakers described ways in which they were engaging others and encouraging them to actively address societal bias, racism, and injustice, as well as cultivate a more inclusive culture, while also mindful of the longstanding anger and suspicion felt across the country in communities of color.

Nilon, who started his graduate studies 10 years after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, sees the current BLM movement as an extension of the outrage then.

“I think that it’s still very difficult in the environmental field for people to really understand why Black lives matter and what that means,” he said, “not in the sense of all the things that are happening right now but in the sense of saying, ‘Why does it matter to engage people that look like us, why is that important, what does our contribution mean?’”

For Lewis, combatting systemic bias and racism first requires everyone to truthfully assess and gain insight on how they are viewing other people if they are to understand how they may be contributing to the problem.

“It’s important for us, collectively, to be honest about implicit bias and the role that implicit bias plays in how we respond to people who are situated differently than us,” she said.

Lewis added that what makes implicit bias particularly pernicious is how freely it can insinuate across peoples, communities, and institutions. She noted that when she was with the Park Service and had her uniform on, it didn’t matter that she was Black, or that she was a woman, she could easily be perceived as “the oppressor” to the people she is encountering.

All the speakers concurred that while engaging others in frank conversations about bias, race, and identity is important, achieving real and lasting societal change requires much more.

“We have to move beyond the idea of saying, ‘Why aren’t Black people in a certain space?’” said Nilon. “The real question is, ‘What is it that engages people, that moves people to action, and how do you bring that into and have the environmental movement recognize that?’”

Lanier wholeheartedly agreed and challenged others to ask themselves if they are truly committed to effecting change or simply wish to be seen as doing so.

“If the goal is only to look good, but there is no impact, then that’s extractive and colonial, and we need to be clear on what our intentions are,” she said.

In spite of the challenges, there was optimism that genuine and lasting change was possible, provided there was sufficient buy-in.

“Listen to the people in your communities,” said Lewis. “Have conversations with those folks and then go beyond those conversations to do the work.”

And, added Lanier, the most important thing is not to quit.

“Be tireless,” she said. “Have it be non-negotiable that you will be successful. You only fail if you give up.”